“My family and I had just moved from the south into a very rural area of Millfield, a former coal mining town in the Appalachian foothills of southeastern Ohio. I’m indigenous Mexican and Filipino, and at the time, racial tension in the country was increasing — especially towards Mexicans. As I watched everything transpire in the news, I started thinking about how the media and news was pointing fingers at people who are my neighbors, saying Appalachians and the rest of Middle America were racist, opposed to any kind of diversity and inclusion, and responsible for what was happening.

Having just moved to the area, I felt I needed to know for myself—what would my experience as a person of color be if I were to go out and meet my neighbors?

Prior to this, I had left my job as a full-time photojournalist a couple years before. Because I was always traveling for work, I missed meeting my neighbors and really getting to know my community. What attracted me to this place in Ohio and what makes it feel like home is that before photojournalism, I was a blue-collar worker. I’ve lived in places like Abu Dhabi and Tucson, but I just feel more connected in a community that’s full of people who are working-class because I still feel like I’m a working-class person.

Besides that, I’ve always been intrigued by questions across history: how did this town or the city come to be? What was the economy behind it? What was the socio-economic state of the region? What is the heritage and culture? I feel like Southeast Ohio is full of a rich history and culture. A big part of that is coal mining, and that intrigued me.

So, between the narrative around increasing racism towards people like me, my attraction to this place, and having just moved to the area, I picked up my camera and thought, ‘Let’s go meet my neighbors.’

I got in my truck, drove around, and got lost on purpose. I photographed a lot of the towns that still exist and some that are now ghost towns. I met and talked with people, and photographed them along the way.

It became a solo driving history tour, and as I was looking at the pictures I was taking, I realized that it was something bigger than my initial intentions. I didn’t go out to consciously document this region from the eyes of a person of color, but it transpired into that.

Throughout my photojournalism career and even early on as a student, I really played down my race. At times, there were opportunities where you could get an internship or position because they were looking for underrepresented minority photojournalists—and I really made an effort not to apply for those roles. I wanted to feel like I was hired for a position because of my merit, not because of what I look like. I needed to prove that to myself.

Initially for this work, I was hesitant to bring in the aspect of being a person of color working in this region, and in fact, I almost left it out because I wanted it to be about this place and not about me.

But I have a very close friend of mine who grew up in this area—a white male—and he kept encouraging me to talk about it and share my perspective as a person of color. He told me that the pictures I made were not the same pictures that he or any other person could make. The interaction between a photographer and a subject—the words, the nonverbal communication—was different because of who I am.

We talked a lot about this, a lot of back and forth because I’ve never been very vocal about being a person of color or about experiencing prejudice or racism.

Part of that reluctance of including my perspective in my work is also inherent in photojournalism—taking yourself out of the process as part of the ethics in journalism. But what was different about this work was that I made a conscious effort to not approach it like a photojournalist, and even though these pictures would become my photobook, Black Diamonds, that wasn’t the initial goal. It was just to meet my community and take some pictures for myself again.

Sometimes we had long conversations and sometimes they were just fleeting moments as I took their portrait, but overall, I felt really well received and welcomed.

But while I was driving around to meet my neighbors and take their photos, the awareness around issues regarding race was rapidly increasing and protests were happening around the country. The timelines of those events and with becoming a person of color in Appalachia and meeting my neighbors merged together, and that’s when the light switch went on.

I recognized that on one hand, this work was a look at these post-industrial coal mining boom towns in Ohio, their people and what they’ve gone through, and what their experience is. But on the other hand, it’s also a look at how this specific region received and accepted me as a person of color.

I have to say that I had a really great experience. I really enjoyed meeting people and connecting with the people in this community, my neighbors. Sometimes we had long conversations and sometimes they were just fleeting moments as I took their portrait, but overall, I felt really well received and welcomed.

It’s not like I woke up one day as a person of color. Obviously, I’ve been this way my whole life and I’ve lived all over the U.S. and abroad in the Middle East. I’ve traveled to over a dozen other countries for assignments.

The racism that I’ve experienced worldwide doesn’t just stop by country, or by town, or by city or region.

It’s always there. Racism is an underlying presence everywhere. If there was an extreme presence of it here, of course, I would have dug a little deeper and shown that in the book. But I wanted to be given an honest and truthful rendition of my personal experiences. I don’t want to discredit anyone who has lived in this area that has had a different experience, but mine was very positive.”

“One of the elements of the photobook was photographing and saying whatever I wanted to say, and being subjective about my approach. If I had been doing it through the lens of a photojournalist or for a news angle, that certainly would not be something I interjected into the photos. In that role, it’s important to remove yourself as much as you can from the process.

But Black Diamonds was an exploration of my community and me opening up and talking about what my experience was like as a person of color. It had been about two years since I had worked on a project that was personal, so this project really was an effort to change the aesthetic of how I approached photography and an effort to move away from photojournalism.

I had long conversations with the publisher to express to them what I was trying to accomplish. In the end, I think there is a balance of traditional documentary work and subjective perspective. I’ve tried to be open about that when I talk about the book—that there are both elements of personal subjectivity and photojournalism—because I did get some pushback from one specific photo editor from a major publication who had some negative feedback about the work. They were looking at it through a purely journalistic lens, but my book Black Diamonds is not intended to be displayed or labeled as a journalistic approach; it is clearly more personal and subjective.

I’ve worked in other communities before like Navajo Nation, the Middle East or in Muslim countries and there is so much potential for misrepresentation of those communities. One of the biggest things I learned working on the book, especially not having photographed in Appalachia before, was how much misrepresentation of Appalachia there is, especially since FDR and the War on Poverty.

That didn’t really click until I started working on the book. In the process of this work, I did a lot of research on Appalachia, read books like ‘What You’re Getting Wrong About Appalachia’ and others that people would recommend. Some that were even out of print but I was able to make a Xerox copy to read at home for myself.

Appalachian Ohio is a place with an entire history of people in the past who have come in, extracted stories based on the narrative they wanted to create then left and gave nothing back.

Even though this was a subjective, personal project, I didn’t want to ever misrepresent somebody or send a message that’s not consistent with what that person or how that community represents themselves. No matter what, I’m not going to be able to satisfy everyone with the work, but I’ve also received a positive response from people who have grown up here in the community and left, or still live in the community. That’s been very rewarding to get that feedback and to hear that they like what I’m doing.

I’m not really concerned about what the world outside of where I live thinks about the work, because these people are my neighbors. I’ll see them again and I want them to think it was done out of respect and dignity for people. One gentleman in the book lives a five-minute walk from my house in a little trailer out in the country. I don’t want to make people feel like I’ve done any injustice to anyone and that’s really challenging to do in a region that’s traditionally been photographed in a way that has been extractive, similar to what happened with our mining communities. Appalachian Ohio is a place with an entire history of people in the past who have come in, extracted stories based on the narrative they wanted to create then left and gave nothing back.

At the end of the day, this book is one person’s experience—my experience. I’m one person in this massive region. There are about 60 photos in the book that try to document a specific time, place, and emotion, so it isn’t an attempt to explain everything about what Appalachia is and who the people are. This is just one small story on a very big rock.”

“Across my whole life, a camera has been an opportunity or tool to learn about a topic, meet people or document something and it all started with skateboarding and a little point-and-shoot camera.

For whatever reason, I was always the guy in our crew with the camera. If I couldn’t afford film, my friends would buy it for me so I could take pictures of us skating, hanging out, and doing tricks. From there, it just spiraled into using a camera as a tool to meet people and to get access to things that I was curious about.

I just wanted to go take pictures. It was as simple as, ‘I’ve got this camera, I see that person and they look really interesting. I want to photograph them. I want to meet them. I want to find out what their story is.’ It’s still so profound and astonishing to me because no matter where I’ve lived, people are usually very receptive to someone with a camera who just wants to know more about who they are and what they’re doing.

It’s just a really wonderful gift that photography offers—the excuse to talk to people. People that normally would not speak with each other get to talk to and get to know someone who might be different.

While I was taking the photographs for Black Diamonds, I was driving down a road and saw a man digging a trench in a little town.

I pulled into his driveway, just enough to get my truck off the road.

‘Do I know you?’ he said as I was walking up to him.

‘No, sir,’ I said.

He asked, ‘Are you with the cable company?’

I said no and introduced myself. I don’t think he heard what I said because he just started talking at me.

He asked me, ‘Are you Mexican? Not that it matters…’

He keeps talking and starts using terms like ‘colored folk’, and at this point, I still haven’t had a chance to ask if I can photograph him.

Finally, I just interrupted and said that I was going to take a few photos while he talked. He didn’t say yes, but he didn’t say no. He just gave me a look like he didn’t care because he wanted to keep talking.

As this was happening, I turned around and saw this huge confederate flag flying in front of his house. I laughed to myself because had I seen it before, I probably would not have stopped and talked with him. When I got my photos, I thanked him and started to leave.

He said, ‘You know, next time you’re driving by and have some time to talk, stop by and knock on the door. Let’s have a beer together.’

For me, maybe the moral of that story is that it’s good that people like myself get out and interact with other people. For all I know, he may have never interacted with another Mexican in his life, I really don’t know. But I think people can be afraid of the unknown, and when something is unknown, it’s easier for people to dislike something or have unjustified feelings towards a group of people.

I think you can look at that situation both ways, and think, ‘Oh, that’s messed up.’ You can just focus on the negative, about that guy being a self-proclaimed racist. Or you can look at the positive, about what he said about wanting to talk and have a beer, and that bringing different people together can open doors and open minds to change who we are as a community and how people see us.”

“As far as how a skateboarding Indigenous Mexican and Filipino photojournalist ended up in rural Appalachian Ohio, we had gone on a cross-country road trip while my wife’s dad was living in Flagstaff, Arizona. There are mountains there, with tons of outdoor things to do. We had a great time going on hikes and checking out creeks and the kids really enjoyed it.

We had a lot of time to talk on the trip back during the drive and my wife suggested that we should move somewhere with mountains, so when we got back, I started looking for a job in Flagstaff. With the cost of living there being higher and a minimal amount of jobs in my field, we chose to keep looking.

Then a job in Athens popped up at the university. Having gone to school there, I was familiar with it. It’s not mountains, but it’s at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

We looked at the cost of living here, the cost of land, and it just seemed like a no-brainer. Everything just kind of fit. With the job qualifications, I just kept checking them all off. It was cool because it was such a tapestry of different skill sets, tailor-made for me. I applied, was offered the position, and we moved.

This was the first place that everyone – my wife, my kids, and myself – felt happy about where we lived and the friendships and relationships that we were building. That was a big deal for us because up until that time, we had moved on average every two to three years. Being in journalism meant we went wherever the next best opportunity was.

We’ve lived here almost six years now, which is the longest we’ve lived anywhere, by far. Before this, we lived in Abu Dhabi for three years and that was the longest we lived anywhere.

What attracted me to this place and what makes it feel like home is that before I became a photojournalist, I was a blue-collar worker. I didn’t go back to college until I was in my late 20s. Prior to that, I did blue-collar work. I feel more connected in a community that’s full of people who are working class. I still feel like I’m a working-class person.

Along with that, there is also a lot of solitude and freedom living in the hills…and being a skateboarder, I built a ramp on my property and I can make as much noise as I want.”

“In the book, I wanted to make sure to show the people here along with the place, but as a photojournalist you typically don’t do a lot of portraiture—it’s more about capturing the moments that tell the story, pull the heartstrings or educate people. Usually, the content will override aesthetic for news organizations.

The aesthetic of a lot of my photojournalism work from that time was more moody, dark with Rembrandt lighting. But when I approached Black Diamonds, the first thing I wanted was to not have really moody lighting. I wanted everything to be kind of neutrally lit and that was beneficial in this region, because it’s almost always overcast.

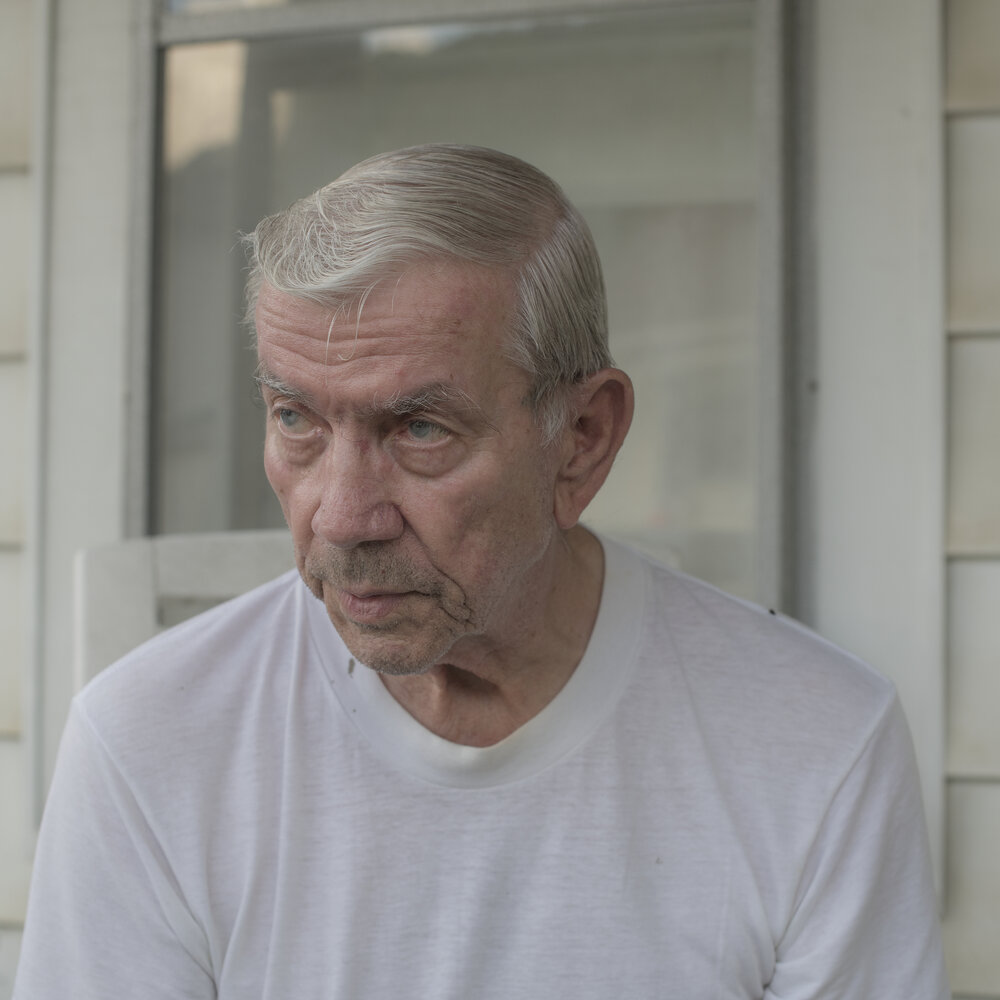

The majority of the book is portraiture because I wanted to encourage the viewer to look these people in the eyes, to look at their faces and have the opportunity to see and meet their neighbors.

I did that purposely because I didn’t want the lighting to sway the way people were perceived. I was definitely aware of how the region was showcased previously, so if I had made the photographs very dark and real moody, or with a lot of tone, that could reinforce lower-income visuals, and there’s already been enough of that done here. I really wanted to show it more from a vernacular perspective—just documenting things in a very straightforward way. There is a lot of photography of Appalachia and most of its very moody, typically focusing on opioid addiction or poverty. That story has been told enough, so it was about changing the aesthetic and the approach.

Quite often, I feel like people in the region are almost invisible. People often don’t acknowledge their existence and just look past them. The majority of the book is portraiture because I wanted to encourage the viewer to look these people in the eyes, to look at their faces and have the opportunity to see and meet their neighbors.”

“Talking about what I think makes a photo and a good photobook, I’m a big stickler about things being technically on point. First of all, it better be sharp. I used to have some graduate assistants working for me, and one of the first things I looked for when I would critique their work was if it was soft. We’d have like these bigger monitors and would blow them up, and I notice if things are not focused correctly. So, for me, the baseline standard is the technical side, and things should be sharp, framed, and exposed correctly.

Beyond the technical side, a great photo resonates with a larger audience. I think a photo is good when it doesn’t have boundaries of the types of people who would appreciate it. It’s not something where one class of people will get it, but another won’t, or you have to be an artist or a photographer to understand that it’s a good photo.

But even I’m guilty of that sometimes with parts of my work. My wife is a big part of the editing process. She sees all my work first and she’s pretty tough. She made the comment to me once that she judges my work based on if she thinks it’s a picture she would take. If it’s something obvious she would see, then she doesn’t like it because she appreciates a new perspective that introduces something different and a new way to look at the world. To me, that’s a really good gauge to measure what makes a successful photograph.

In photojournalism, often they will only take one photo, especially if the content is similar, such as buildings. What I love about bookmaking is that you can craft a narrative differently in a way that creates a new story. It represents a new visual voice or poem within your larger body of work.

As I’m shooting, I’m always building the narrative in my head. I’m shooting more in terms of linking images together to build a larger message.

When it comes to photo books, I think it starts with how you approach the production of a book. In the past you see a lot of these coffee table books with a really poorly designed cover and poor materials, and they just literally sit on someone’s coffee table. That’s not very interesting to me. I have nothing against them and there’s a place for those types of books. But often, they are not shot with the intention of showing a narrative from one voice or one vision.

I’m interested in photo books that are art objects within themselves. It’s not about just the photographs and it’s not a photo book—the book itself can be a piece of art.

I think you do that by the selection of your textiles for the cover, if you emboss or if you do a letterpress. Then when you go inside, what do the pages feel like? What is binding like? Is there back matter in terms of an index and an essay?

Taking that approach of a photo book as a conceptual art project, where the photos are certainly a driving force in the book.

I just do what I do and hope that people enjoy it and if they don’t, that’s okay. There is work I do that I get paid for like with the university or the New York Times. Then there is the work I do for myself. I don’t make any money off the work I do for myself and that’s fine.

It gives me more freedom and I can do whatever I want. I don’t have a deadline. I don’t have anyone with any sort of expectations of me. I answer this to myself and that’s the beauty of it.

It’s just the love of the act of making photographs, exploring, learning, and growing as a photographer. Back when I started, there weren’t things like Instagram. Even when I started taking pictures here for what would become Black Diamonds, there was no underlying goal for the work other than to meet my community and get out there and take some pictures for myself again.”

— Rich-Joseph Facun, author of the photobook Black Diamonds

Millfield, Athens County

#WeAreOhioSE