- The Appalachian region is beginning to attract investment in petrochemical facilities.

- Growing natural gas production in the region is a major draw for chemical companies, which use fossil fuel byproducts to make plastics.

- A second petrochemical hub in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia would compete with facilities on the U.S. Gulf coast and create thousands of jobs.

The natural gas boom has enriched northern Appalachian states, and now the region reeling from the decline of the coal industry is hoping the surge in fossil fuel production will help it feed the world’s growing demand for plastics and chemicals.

The U.S. shale drilling revolution is fueling a wave of investment in U.S. petrochemical plants, the facilities that use byproducts from oil and natural gas production to create the building blocks for plastics.

Since 2010, 301 chemical industry projects worth $181 billion have been announced in the United States, according to the American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing U.S. chemical companies.

“In our opinion, we’re going to struggle to meet that level of demand growth, even with all the assets we see going in in North America.”

Appalachia’s share of the planned investment is relatively small, at roughly $16 billion. But the American Chemistry Council and regional boosters believe states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia are positioned to capitalize on growing demand for plastics around the world.

“It’s really a race to capture global share,” said Paul Boulier, vice president of industry and innovation at Team NEO, a northeast Ohio economic development organization. “From our little part of the world, we want to get a bigger piece of that pie.”

Among the slices it has already carved out are a Royal Dutch Shell petrochemicals complex along the Ohio River in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Shell expects to begin construction next year and says the project will create 600 permanent positions and about 6,000 construction jobs.

Rendering of Shell’s Pennsylvania petrochemical complex

Source: Shell Oil

Down the Ohio River, another multibillion-dollar facility could rise in Belmont County, Ohio. Thailand’s state-owned oil-and-gas giant PTT is behind the project and says it will make a final investment decision by the end of the year.

This would provide much needed relief for Belmont County, where the unemployment rate was 5.7 percent in May — among the highest in the state. The median annual income was $43,833 between 2011 and 2015, more than $10,000 below the U.S. median.

But Boulier and other boosters believe the two facilities are just the start. The American Chemistry Council envisions a regional transportation and storage hub that could create tens of billions of dollars in economic expansion and about 100,000 jobs.

Appalachia’s advantage

The formula is fairly simple. The Marcellus and Utica shale formations, two of the biggest natural gas fields in the United States, largely lie beneath Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and New York. The surrounding Rust Belt is also home to many of the country’s plastics manufacturing factories.

What’s missing is the link between the two: the massive plants that turn natural gas byproducts into the inputs needed to manufacture plastic products.

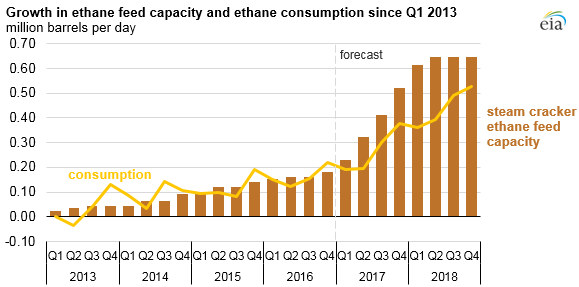

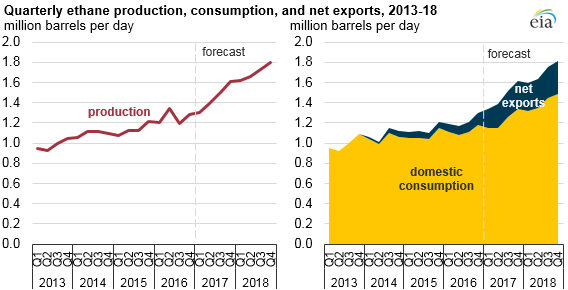

The plants, called crackers, heat natural gas byproducts, like ethane and propane, in order to break them down, or “crack” them, in industry parlance. What comes out is base chemicals, like ethylene and polyethylene, the most widely used plastic, which is shipped in pellets that are then shaped into a range of consumer and industrial goods.

The Shell facility near Pittsburgh will use ethane produced in the Marcellus and Utica basins to make 1.6 million tons of polyethylene a year. The oil major notes that “more than 70 percent of North American polyethylene customers are within a 700-mile radius of Pittsburgh.”

Shell will no doubt seek to tap that domestic market, but the crackers already supplying the region will certainly fight to keep their share, said Steve Zinger, vice president of chemicals at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. The result: Much of the new net output will likely be exported, he said.

This is one reason big companies with logistics experience like Shell will continue to drive the petrochemicals expansion, Zinger said. Already, plans for small crackers in the Appalachian region have been scrapped or delayed.

“You really need those economies of scale. You can’t just go on the feedstock alone,” Zinger told CNBC.

“It’s one thing to have the technology to convert ethane into a chemical, but then you have to say, What am I going to do with this chemical? How am I going to move it to market?”

A world hungry for plastics

The good news is the long-term prospects for the petrochemicals industry remain strong, according to Zinger. Rising demand for food packaging and consumer products in emerging markets will offset the push for more recycling and judicious use of plastics in the developed world for years to come, he said.

Demand for ethylene typically grows at about 1.3 times the rate of global economic growth, said Mark Eramo, vice president of global chemical business development at IHS Markit. Assuming 2.5 percent to 3 percent GDP growth, demand for ethylene will rise by 5.5 million to 6 million tons a year, he said.

“In our opinion, we’re going to struggle to meet that level of demand growth, even with all the assets we see going in in North America” and around the world, he said. “We don’t see any dark clouds, barring an economic meltdown.”

While the Appalachian region has convenient access to natural gas, Eramo believes companies investing billions of dollars into crackers will continue to think twice about investing there because it lacks the network of plants, pipelines and storage facilities present in the Gulf. Companies like Exxon Mobil and Dow Chemical have opted to build new facilities in the Gulf.

The American Chemistry Council acknowledges it’s uncertain how a second transportation and storage hub in Appalachia would be financed. It’s something of a chicken-and-egg situation: The region needs infrastructure to attract petrochemical facilities, but it’s hard to get financing for infrastructure without the facilities.

The council created a scenario in which the region builds a hub, including five world-scale crackers, storage facilities and pipelines. It found it would require $32.4 billion in capital investment.

Earlier this year, West Virginia Sen. Shelley Moore Capito introduced legislation that directs the Energy and Commerce departments to study the feasibility of building an underground ethane storage and transportation hub in the Appalachian region.

It took about 60 years for the Gulf to develop into the highly integrated petrochemical hub it is today. Boulier believes the Appalachian region can develop one in much less time, maybe just 15 years, partly by planning the system as a whole. The United States has also become a leader in producing cheap natural gas byproducts in recent years, making it attractive to investors, he said.

States eager to grow jobs are likely to offer generous sweeteners. The tax incentives offered to Shell to build the Beaver Country cracker amount to $1.6 billion over 25 years, Pennsylvania lawmakers estimated.

From CNBC | July 11, 2017